The Third Iteration of Monotheism : Christianity - From a Jewish Heresy to a World Religion

I discuss about the spread of Christianity - from its origins as a Jewish sect to a world religion with an insatiable hunger for converts and detail its interactions with polytheism.

Jewish Context & the Historical Jesus

Christianity is not the religion of Jesus. The religion of Jesus was Judaism. Jesus was Jewish in every sense - he was circumcised, kept kosher, read his Bible in Hebrew, spoke Aramaic, believed that the entire Torah was binding law, and celebrated only the Jewish festivals - the Passover, the Pentecost, Yom Kippur, Hanukkah, and the Jewish New Year. Christianity is the religion about Jesus, not the religion of Jesus.

In the first century when Jesus lived, the region of Israel was under the rule of the Roman Empire either through puppet kings or direct governors. The Jews had been under Babylonian, Persian, and Greek rule for centuries when finally they had fought for independence and established the Hasmonean kingdom after the Maccabean Revolt against the Greeks. But the Romans a few decades back had conquered Israel and this created a huge resentment against the Romans in the minds of Jews. The Romans also collected a lot of taxes from the people like any other large empire which also fuelled it. While some Jewish sects physically fought against the empire by combat or terrorism (like the Zealots), some other sects did a passive religious warfare. These sects described by the adjective “apocalyptic” had charismatic leaders who claimed that God himself would send a descendant of David who would fight the Romans and establish the Kingdom of God in Israel. In Jewish culture, kings of Israel are coronated by getting anointed with oil. Hence, the title to refer to the king of Israel was the word “māšîaḥ” which literally means “the anointed one” from which we get the word messiah. The translation of the word messiah into Greek was the word “Christos” which meant anointed in that language.

Thus, proclaiming someone as the “messiah” or “Christos” in the first century meant that he would defeat the enemies of Israel and establish God’s kingdom there. This is what the followers of Jesus from Galilee thought so too. But Jesus, like many other messianic claimants, got captured by the Roman authorities and was crucified for claiming to be “The King of the Jews” as the title messiah meant.

From this point of view, the crucifixion of Jesus would have been a devastating news for his followers who saw their messianic plan go to complete ruin. But, the followers of Jesus eventually came to believe that he had been raised from the dead and that his death was not a mishap of justice but for the justification of the sins of Israel. In Jewish theology as in many others religions, animal sacrifices were accepted by God to atone for sins. The apostles of Jesus came to believe that his death on the cross was a human sacrifice and faith in that would lead to the atonement of one’s sins and put one in a right relationship with God. They also believed that Jesus would return soon a second time (The Second Coming of Christ) for establishing the kingdom of God that was promised the first time and within that, they had to spread the good news (Greek : evangelium) about this sacrificial atonement to others. The apostles took random Biblical verses out of context and interpreted them as predictions of Jesus. But, most Jews simply rejected this message as they could not be convinced of a messiah that was crucified.

Paul : The Apostle to the Gentiles

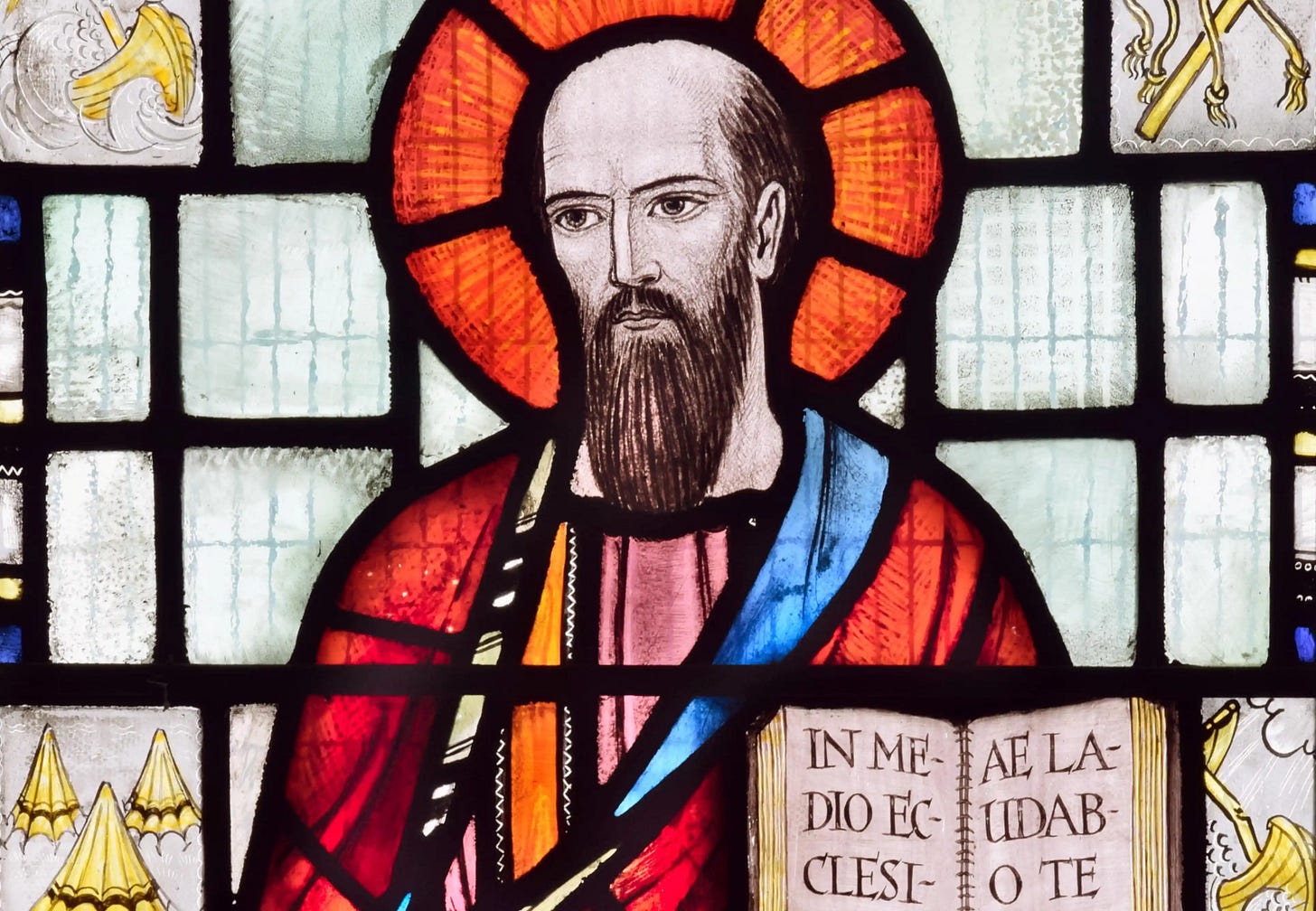

Christianity did not amount to much as a Jewish sect and was widely rejected as a heresy. The real success of Christianity would come about when it was taken out of its original Jewish context and supplanted in the wider gentile (non Jewish) world. While Christianity was failing as a Jewish sect based on a crucified Jewish messiah, a devout Pharisaic Jew named Paul of Tarsus had the perfect epiphany to make it into a world religion. He proposed that faith in Jesus as the atoning messiah was not just open to the Jews (the original chosen people of God as per the Hebrew Bible) but for all humans.

Paul also argued that because of the crucifixion of Jesus, the ritualistic part of the Jewish law (including circumcision, kosher diet regulations, keeping the Sabbath, animal sacrifice, and other rituals) in the Hebrew scriptures had been transcended and substituted for through faith in Jesus.

The brilliancy in the rhetoric of Paul can be seen in his letter to the Romans (in the New Testament) where he argues using the Jewish scriptures themselves that the Jewish law (in those very same scriptures) was not that important to Judaism! The central crux of Paul’s argument is that God chose and blessed Abraham’s descendants as his own people after observing how steadfast Abraham was in his faith. Only after that, he commanded circumcision of himself and his male descendants. Paul understands this to imply that it was faith that first made Abraham upright in the eyes of God ; the commandment of circumcision came later. For Paul, the fundamental essence of Judaism is that of the relationship between Abraham and God through his faith. All the other things - circumcision and other laws revealed at Mt Sinai through Moses - all these came later. So, Paul justified that when he was grafting gentiles into the chosen people of God and proclaiming that faith in Jesus was enough for gentiles to be chosen and partake in the blessings of God, he was not violating or blaspheming against Judaism (as most other Jews thought) but was returning Judaism to its primordial original Abrahamic essence. He also interprets the verse in Genesis where God blesses Abraham saying “all peoples on earth will be blessed through you”, this actually was fulfilled when the gentiles from other nations joined the Christian movement with just their faith in Jesus. So, according to Paul, the Christian Church was not a heresy of Judaism but the fulfilment of Judaism and a return to its original essence.

This enabled non-Jews to join the cult very easily since they could now retain their culture while subscribing to faith in Christ, instead of converting themselves to Judaism and keeping up the complex law codes of Judaism. This enraged Jews even more - not only were Jesus followers proclaiming a crucified messiah, but they were also bringing gentiles (non Jews) to their sect, and that too, without making them keep up any Jewish law. This soon caused a schism between Judaism and Christianity with both going their separate ways.

Judaism would henceforth continue to uphold its ethnic identity, ritual purity, and develop Rabbinical interpretations of scripture to maintain being a culturally rooted faith while Christianity would go on to become a world religion seeking converts around the world and interpreting the Jewish scriptures as typologies prefiguring the arrival of Jesus Christ.

Paul himself went on missionary journeys throughout various important cities of the Roman Empire to convert gentiles into Christianity and some of the letters he wrote to the churches he founded or hoped to visit ended up getting preserved in the epistles of the New Testament. The following was a list of cities that Paul toured based on the geographical information provided in his epistles and the Book of Acts.

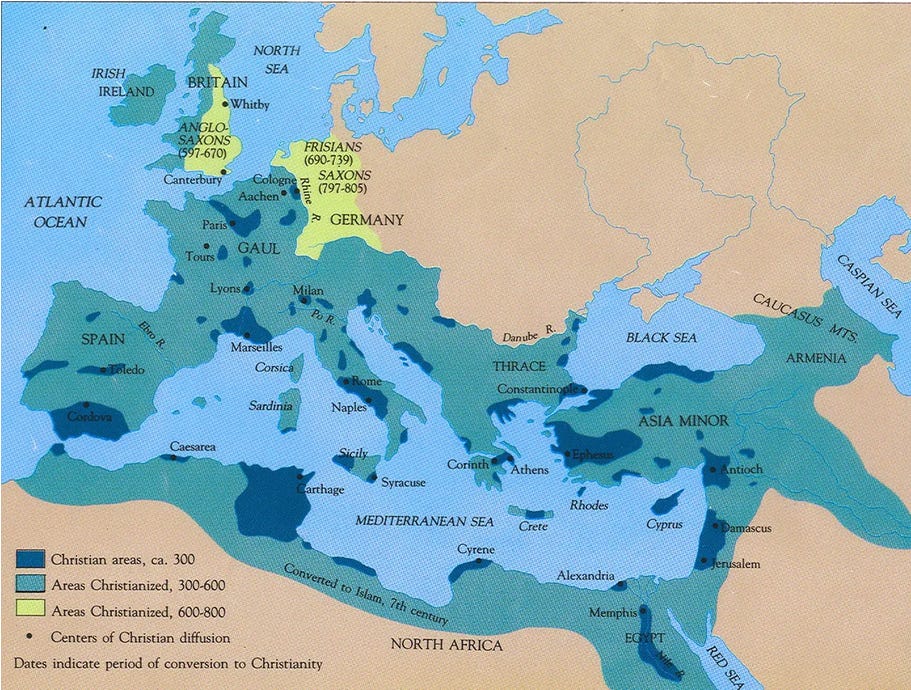

Despite the occasional persecution, Christianity would continue spreading mainly in the cities targeting mostly the poor, desolate and the socially stigmatised members of the society (widows, orphans, prostitutes, new immigrants to cities, etc…). From the map below, you can see this phenomenon. The fact that Christianity would be a city based religion initially is evident from the term that Western Christians used to refer to the unconverted population from the fourth century onwards - pagan. The word “pagan” comes from the Latin word “paganus” which itself means someone who is a resident of the “pagus” which means a village in Latin. The fact that Christians regarded unconverted peoples as villagers tells us that pagans were predominant in the villages at that time.

Christian polemic against paganism

We saw in a previous article that Judaism was monotheistic which means that they believed that only one God existed. They initially thought that the gods of other nations are “lesser spirits” but by the time of the prophets, they had come to believe that other deities of other peoples are just dead idols. But still, they did not go about proselytising because they also strongly believed that this one God had specifically chosen the Jewish people (descendants of Abraham) and not other nations. So, because of this, Judaism still had lot in common with the wider world of paganism except the monotheistic aspect. They are :

Worship in a temple : Jews worshipped their god Yahweh in the temple at Jerusalem (first built by King Solomon) where they believed that the spirit of Yahweh existed. There are several times where Solomon’s temple is referred to as “the house of God” in the Bible. Just that temple did not house an idol of the deity (as in paganism) but housed the ark of the covenant.

Rituals & Sacrifices : Like in pagan religions, rituals and sacrifices (both material and animal) to God were a regular occurrence in the Jerusalem temple.

Ethnic religion : As said, like paganism, Judaism too was an ethnic religion based on birth and Jews identified as Jews because they shared common origins and history from the ancient nation of Judea. This made evangelism unnecessary.

But unlike paganism, Judaism was a transnational religion with adherents throughout the Roman Empire (thanks to the diaspora of Jews who were scattered all over the known world ever since the Babylonian conquest of Judea in 586 BCE). Any Jew no matter where he went, could walk into the synagogue there and instantly make connections and get around. This could not be said about paganism which was local. Seeing the tightly knit Jewish community, some pagans (gentiles) were attracted and joined the synagogue. But they could never become fully Jewish as they found Jewish rituals and law codes tough to adapt (circumcision was not a pleasant operation for adult males in the ancient world and the kosher diet rules would also be too restrictive to prospective converts) and Judaism was still an ethnic faith. But they did participate in the synagogue and were called by the Jews as “God-fearing gentiles”. When these god-fearers saw Christianity, a Jewish sect that was open for all and exempted converts from the Jewish law, these would be the first people to convert to the new faith.

From the beginning, the early Church did not want to join in with the syncretic religious sects of the Roman Empire. When Christians looked around the pagan religious activities going on around them like veneration of ancestors, worship of nature, pick-and-choose approach to religion, they described what they saw as “paganism”. Christian theologians polemically targeted three particular practices that they saw as demarcating the false pagan religions from the universal and true Christian religion. They are :

Polytheism

Idolatry

Sacrifice (material / animal / human)

Polytheism

Demarcating line between true and false religions

The worship of multiple deities rather than one was the first fundamental demarcation between paganism on the one hand and Judaism and Christianity on the other hand. The Jewish pre-Christian philosopher Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE - 50 CE) was the one who coined the term “polytheism” as a means of demarcating the difference between the false pagan religions and the true religion of Judaism. Once Christianity had become the official and eventually the only tolerated religion of the Roman Empire, pagan apologists began to devise defences of the validity of paganism by arguing that pagans too worshipped one ultimate higher power in different forms rather than different deities.

Polytheism as an ultimate monotheism

But already for a long time, the philosophically minded of the Greco-Romans had expressed this. According to the historian Plutarch (46 - 120 CE) :

There are not different gods for different peoples; not barbarous gods and Greek gods, northern gods and southern gods … however numerous may be the names by which they are known, so there is but one Intelligence reigning over the world, one Providence which rules it, and the same powers are at work everywhere. Only the names change, as do the forms of worship.

In the famous novel “The Golden Ass” by the philosopher Apuleius (125 - 180 CE), he describes the Egyptian goddess Isis appearing to the main character in a dream announcing :

I am the single power which the world worships in many shapes, by various cults, under various names.

Neoplatonism : The pagan competitor to Early Christianity

In the 3rd century CE, the Greek philosopher Plotinus founded a new branch of philosophy now called Neoplatonism whose central religious teaching was that the source of all existence was an entity called “The One” who emanated the cosmos. Life was an internal spiritual journey in quest for ascent of the soul (Greek : anabasis) with “The One” (Greek : to hen). While Plotinus was less focused on ritual than his successors, he acknowledged that popular religious practices could serve as meditative aids to direct the soul inward and upward toward the One. For instance, sacrifices or prayers might symbolise the soul’s offering of itself to higher realities, facilitating contemplation.

One of his adherents amend Porphyry (regarded by Christians of his time and beyond as their most bitter enemy) in his work “On Cult Statues” sought to rationalise traditional polytheistic worship by interpreting myths and religious practices through a philosophical lens, thereby seeking to reconcile popular belief with philosophical standards. He saw myths as accessible ways to convey complex metaphysical ideas to those not trained in philosophy. While his works like “Philosophy from Oracles” legitimised polytheistic worship by suggesting it could aid in a soul’s salvation, Porphyry ultimately viewed the Olympian gods as relatively low-ranking beings, separate from the highest, singular divine principle. His philosophy aimed to understand and justify polytheistic rituals, even the most superstitious ones, by revealing their underlying philosophical meanings. For Porphyry, myths were not historical accounts but allegories of cosmic and spiritual processes. Porphyry’s work “Against the Christians” (now largely lost except for quotations by Christian authors) critiqued Christian literalism while defending pagan traditions as philosophically sophisticated. He argued that pagan myths, when properly interpreted, revealed universal truths about the cosmos, unlike the historical and literal claims of Christianity.

Iamblichus, a student of Porphyry emphasised the notion of theurgy (divine work), a ritual practice aimed at invoking divine powers to aid the soul’s ascent. In works like “On the Mysteries”, he provided a robust defence of pagan rites and myths, integrating them into Neoplatonic metaphysics. Iamblichus argued that rituals were not merely symbolic but actively facilitated the soul’s connection to the divine. Theurgy involved invoking divine powers through specific rites, symbols, and incantations, which he believed were established by the gods themselves. For Iamblichus, myths and rituals were divinely inspired and contained symbola (tokens or signs) that resonated with the divine order. Like Porphyry, Iamblichus saw myths as allegorical, but he placed greater emphasis on their divine origin. He argued that myths were not human inventions but revelations from the gods, encoded with truths about the cosmos. For example, stories of gods and heroes could represent the interactions between higher and lower levels of reality. For more details about theurgy and its parallels with Eastern traditions like tantra, read this interesting book here.

Neoplatonism provided a clear theology for the expression of monotheistic principles, thereby challenging the exclusivity of the Judaeo-Christian religions in this sphere, while at the same time also accommodating and rationalising all popular religious traditions and myths. Neoplatonists were problematic for Christians also because they did not fit the standard Christian stereotype of the pagan as a blood-thirsty unsophisticated barbarian. For instance, Porphyry was a highly educated Pythagorean and hence argued against blood sacrifice of animals (like Christians were) and espoused vegetarianism as essential for spiritual health. Neoplatonic philosophy would have a major influence on religious, magical, and scientific thought in the European Renaissance.

Idolatry

Christians have always loved to accuse pagans of idolatry. The Second Commandment orders “‘You shall not make for yourself any graven image … You shall not worship them or serve them”. The word “idolatry” derives from two Greek words “idos” (meaning : form) and “latria” (meaning : worship). An idol is a physical manifestation of God in a certain form. In this sense, idolatry was common to all ancient religions. Idols could come in many times. They could either be

Natural feature : like a stone, rock, tree, mountain, spring, river, grove that are purely natural or lightly adorned.

Statue : of wood or metal or stone

The chopping down of sacred trees is a common theme in many Christian hagiographies. Germanic peoples were particularly partial to tree worship and according to the Roman historian Tacitus (56 - 117 CE), they rejected the notion of housing their idols in built structures or temples, and believed that trees in their natural environment provided the closest link between humans and the gods. The Celts were more prone to worship in sacred groves (natural and semi-natural) and water springs and also worshipped columns or wooden posts as representations of sacred trees. Stone pillars, interpretable as representing tree trunks, were also venerated across much of the Mediterranean world. These could be plain or inscribed with symbols and dedications. Sacred mountains abound in all pagan cultures and even in Judaism with for example Mt Sinai where Moses got the commandments from God. The city of Jerusalem itself was sacred in Judaism because it was at a higher altitude from the rest of the region and hence referred to as “the city on the hill”. This is also seen in Christianity with notions like Jesus’ “the sermon on the mount”. The Greeks and Romans were more famous for their stone idols that required extensive and intricate craftsmanship. These were housed in big public temples and attracted daily ritual attention by priests.

Sacrifice

In the eyes of Christianity, the practice of sacrifice (especially blood sacrifice) was another essential line of demarcation between their faith on the one hand and that of the pagans and even the Jews (the Jews too were practising animal sacrifice in the temple at Jerusalem till 70 CE when it was destroyed and also at their homes through ritual kosher slaughter) on the other hand.

Material Sacrifice

A part of the harvested crops or processed foods were routinely offered to the pagan gods both in temples and houses that were either burnt or simply left to decompose. They also could be thrown into sacred rivers, pools, and springs. In Greco-Roman worship, libations (liquid offerings) of wine, beer, oil, and honey were common. These libations could be simply poured on a sacred site or on the idol or more elaborately presented in special vessels through extensive rituals. Intimate personal objects like jewellery too were offered to the gods and also hair and clothing. Leaving coins at temple sites or inside sacred water bodies were common too and these practises have been carried forward into Catholic Christianity as well. Weapons and other military equipment too make up a large proportion of offerings, and have been found in wetland and river sites across Europe. One intriguing aspect of such deposits is that the weapons were often apparently deliberately broken or bent, in other words rendered ineffective.

Animal Sacrifice

There were two types of animal sacrifice practised in the pagan world - unconsumed & consumed. In unconsumed sacrifice, the animal was offered to the gods by burning them or burying them at sacred sites. This actually constituted a sacrifice from the side of those offering. In the consumed sacrifice, animals were offered up to the gods and then were ritually feasted upon afterwards. A mix of both also was possible wherein some parts of the animal were reserved for ritual feasting and other parts were offered up to the gods.

The Christian god too required blood sacrifice but the crucial difference is that in their eyes, the only blood sacrifice they recognised was the ultimate sacrifice made by Christ on the cross who shed his blood to save humanity from sins. So, they would not recognise any other sacrifice and portrayed them as barbaric and based on blood lust. To pain an even more horrible picture of paganism, the early church writers cooked up examples on how the Greeks and Romans had sacrificed animals and even humans to their gods before the light shed by Christianity. Christians as early from the time of Paul himself, denounced the eating of meat from animals sacrificed to pagan deities.

The Council of Elvira, convened in Spain, in the early 4th century (300 - 306 CE), decreed that Christian landowners should not accept as payment any animal and grain that had been dedicated to idols. In 541 CE, the Council of Orleans also decreed :

If anyone, after receiving the sacrament of baptism, goes back to consuming food immolated to demons, as though he were going back to vomit; if he does not comply with a warning from a priest to correct this collusion, he shall be suspended from the Catholic communion as punishment for his sacrilege.

Human Sacrifice

There is no clear proof that human sacrifice was ever practised in ancient Greece or Rome apart from some exceptional reports. In fact, from what we read in Graeco-Roman literature, human sacrifice was generally understood to be a feature of “bad religion” associated with “barbarians”. The Greeks had tales of accusations of human sacrifice being practised by those who lived on the edges of their known world. For example, in the 6th century BCE, there were Greek stories circulating about Taurians, a people associated with the Crimea, who sacrificed captured Greek sailors to their goddess. The Greeks and Romans accused many of their enemies - e.g. Carthaginians and Gauls - of carrying human sacrifices. The 4th century BCE playwright Sopater wrote about the Celts :

Among them it is the custom, whenever they win any success in battle, to sacrifice their captives to the gods.

The Carthaginians were also widely accused to have practised sacrifice of children. But how sure can we be of such practises when the only literary sources that attest this are from the outsider Greeks and Romans? Archaeological evidence is ambiguous to interpret. Excavations in Carthage, Tunisia, and other towns in the region, have uncovered tophets (dedicated to the god Baal or Tanit), which are stone enclosures in which thousands of sealed urns containing the burnt bones of infants were buried. Some of the urns also contained beads, amulets, and bird bones. These would seem to support the Roman accounts of Carthaginian child sacrifice but the tophets could simply be a cemetery for infants as well whose were then dedicated to the gods. As for the Celts, the English bog body known as Lindow Man who received lethal blows to the head, and his jugular vein cut, with his body placed face down in a shallow pool in a marsh in Cheshire, has been debated extensively. Is this a conclusive proof of Celtic human sacrifice? Again, this is hard to say. It is just as likely that he was the victim of a ritualised killing, which is not necessarily the same thing as human sacrifice. Lindow Man could have been a murderer, or have committed some other vile crime, who was then subject to a ritualised capital punishment. In London, as late as 1834, the corpse of the brutal murderer Nicholas Steinberg was laid face down in his grave and his skull smashed with a large mallet to this end but this does not mean that English Christians practised human sacrifice in the 19th century if some future archaeologist dug him up.

The accusation of human sacrifice hence needs to be taken with a large pinch of salt because this was an aspect of the self definition of Greeks and Romans who identified a set of unacceptable practices (that included human sacrifice, orgiastic debauchery, etc…) that could be attributed to all the “barbarian others” outside their own civilisational ambit. The Christians merely continued this practice for their own self-definition against paganism. This is not to say that human sacrifice was never practised at all anytime and anywhere. There are conclusive examples from other continents in other times. Just that the historic sources from outsider accounts cannot be relied upon, and that archaeology is inconclusive without any contemporary literary evidence from the inside.

Pagan rumours of Christians

The Roman world was full of hot gossip and rumours about the new religion of Christianity which was considered a mysterious middle Eastern cult. The practise of other religions of the Roman Empire were generally heavily public affairs with temples and celebrations out in the open that were inclusive spectacles. But Christian worship was portrayed as being nocturnal, secretive, exclusive and elusive. This was partly true as the early Christians met in house churches (the house of a rich convert that was used for Christian worship). In a dialogue written around 200 CE by a Christian apologist and lawyer named Minucius Felix, the entire spectrum of accusations against Christians is described. Some of them is given below :

[Christians are] a people skulking and shunning the light, silent in public, but garrulous in corners. They despise the temples as dead-houses, they reject gods, they laugh at sacred things.’ … They worshipped the genitals of their priests and the head of an ass … An infant [that is] covered over with meal, [so] that it may deceive the unwary, is placed before him who is to be stained with their rites, this infant is slain by the young pupil, who has been urged on as if to harmless blows on the surface of the meal, with dark and secret wounds. Thirstily – O horror! They lick up its blood, eagerly they divide its limbs.

These are the sorts of activities of which Christians would then subsequently accuse pagans and Jews of carrying out, with equal relish. Of course, except for the bolded parts, none of the rest are plausibly true but we can tell the source of such rumours for some of them. One obvious source of the tales of cannibalism was a misunderstanding of the Eucharist and the consumption of the trans-substantiated bread and wine as the body and blood of Christ. Then there was the holy kiss. ‘Greet all the brethren with a holy kiss’ says Paul in the New Testament. It was easy for this act to attract libidinous rumours of debauchery and orgies. The rumours for ritual orgies and incest could all be influenced by the fact that Romans could not distinguish between Christianity from other mystery religions of the Middle East that attracted more credible rumours of debauchery.

Christians themselves propagated such rumours against other heretic Christian sects (particularly the Gnostics). One such sect of the Carpocratians were accused of hosting orgiastic love feasts and the Phibionites were accused to practise a form of Eucharist that required the feasting of menstrual blood and semen as the blood of Christ (instead of wine). The 4th century church father Epiphanius writes about a heretic sect that used the following technique to prevent their female followers from being impregnated during their sexual worship. If anyone were to become pregnant, then he writes :

… They pull out the embryo in the time when they can reach it with the hand. They take out this unborn child and in a mortar pound it with a pestle and into this mix honey and pepper and certain other spices and myrrh, in order that it may not nauseate them, and then they come together, all this company of swine and dogs, and each communicates with a finger from the bruised child.

Who knows whether any of these groups were involved in anything close to such activities. What these accounts do show however is that there was a set of activities that were unacceptable to the wider Roman world alike - human sacrifice, cannibalism, sexual orgies, etc. Each side used these as propaganda weapons by accusing the other of such activities : Christians against pagans and heretics, pagans against Christians, Romans against barbarians, and so on.

So, such outsider accounts should never be trusted when it comes to deciding on such accusations.

Daimones, Demons & Paganism

How exactly did early Christians in the Roman Empire view the sacred topography of paganism that pervaded the entire known world hosting gods whose memories stretched back to times immemorial? In the case of Judaism, in the Bible, the gods of the pagans are first demoted to “lower divinites” who are subservient under Yahweh, the God of Israel. Then, their divinities are rejected. By the time of the prophets, one sees the notion that the gods of the pagans are powerless idols.

When the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek as the Septuagint, the Hebrew word for “lower divinities” was translated into Greek as “daimones”. This Greek word “daimon” is from where we get the English word “demon” from. But in the ancient Greek world, “daimones” were spirits who are not as powerful as gods but still much more powerful than humans and more accessible to mankind and were in charge of many aspects of the world (especially the spirits of the humans that they possessed). The Greek word for well-being is “eudaimonia” which literally means “good spirit”. These daimones were regularly prayed to and were not bad in any sense as the English word “demon” might have us guess.

Modern European Christians think of Christianity as their traditional and natural religion now since it has been two thousand years from the birth of Christ but the pagans who converted to Christianity in late antiquity not only knew as a mere matter of knowledge but were deeply stung by the fact that Christianity was a novel religion whose God and Lord were unknown to their ancestors who have been worshiping their deities in the form of idols housed in temples for thousands of years. Their ancestors did not know of Christ because he was not yet born but how could they not know about the one true God who had revealed himself to the Jews?

How could the one true God who created the universe reveal himself only to the tiny tribes of Jews? This can’t be the case. In Romans 1:18-32 of the New Testament, Paul says that God revealed himself to all the nations and every nation had once known the one true God of the Bible. It was later that they fell away from the knowledge of that true God into the worship of idols. Why did that happen?

Why did all nations descend into complete ignorance of the true God and slip into the sin of idolatry for thousands of years? It must not have been something normal. Something must have been responsible for it. There must be some force that makes humans slip into idolatry. Even in the Old Testament itself, Jews themselves are seen repeatedly slipping into idolatry despite continuous revelations from God through their prophets. So, it cannot be that the idols are just mere dead pieces of matter as the Jewish prophets had thought. There must indeed be something powerful about these deities in idols, that had made their ancestors worship them for thousands of years. They can’t be lesser divinities or dead pieces of material.

It is now where the Devil comes in. Christians had inherited the notion of the Devil from first century apocalyptic Judaism who was a cosmic enemy figure of God and tempts humanity away from God. For Christians, ignorance and sin of humans are seen arising due to the influence of the Devil. What could be more ignorant and sinful than the ignorance of and turning away from the worship of God? Christians therefore came to see that the idols that inhabited pagan temples were not mere dead matter but as the residence of the agents of the Devil. They took the notion from the Old Testament that the gods of the pagans are “daimones” but Christians reinterpreted the word “daimon” as an agent of the Devil.

So, according to the Christians of the ancient world, the “error” of paganism that had misled humanity for thousands of years was due to the power of the Devil and hence hence when they read the verses that referred to the gods of gentiles as “daimones”, they began to understand it as “agents of the Devil”. This gives us the current connotation of the English word “demon” as an agent of the Devil.

For Christians, the worst among the demons were to be found in the temples of pagans because they were so powerful enough to lead their ancestors away from the true God since times immemorial. In the eyes of Christian writers, Jupiter, Athena, Aphrodite, all of these gods worshiped by their ancestors were demonic. Christian preachers (and writers) time and again reminded their congregation (and readers) in violently instigating language that the ‘error’ of paganism was demonically inspired and that it was demons who first put the ‘delusion’ of “other religions” into the minds of humans and had foisted these “gods” upon “the seduced and ensnared minds of human beings”. These demons wanted human followers, who would feed and nourish them through sacrifices. For Christians, these demons had created the various pagan religious systems throughout the world for not this purpose but also to turn aside people from the true Christian God. Various fantastic theories were given to illustrate how these demons could sometimes predict prophecies correctly, do miracles, and inspire what felt like wisdom. As an example, quoting the early Christian apologist Tertullian in Apology, Chapter 22

And we affirm indeed the existence of certain spiritual essences; nor is their name unfamiliar. The philosophers acknowledge there are demons; Socrates himself waiting on a demon’s will. Why not? Since it is said an evil spirit attached itself specially to him even from his childhood — turning his mind no doubt from what was good. The poets are all acquainted with demons too; even the ignorant common people make frequent use of them in cursing. In fact, they call upon Satan, the demon-chief, in their execrations, as though from some instinctive soul-knowledge of him. Plato also admits the existence of angels. The dealers in magic, no less, come forward as witnesses to the existence of both kinds of spirits. We are instructed, moreover, by our sacred books how from certain angels, who fell of their own free-will, there sprang a more wicked demon-brood, condemned of God along with the authors of their race, and that chief we have referred to. It will for the present be enough, however, that some account is given of their work. Their great business is the ruin of mankind. So, from the very first, spiritual wickedness sought our destruction. They inflict, accordingly, upon our bodies diseases and other grievous calamities, while by violent assaults they hurry the soul into sudden and extraordinary excesses. Their marvellous subtleness and tenuity give them access to both parts of our nature. As spiritual, they can do no harm; for, invisible and intangible, we are not cognizant of their action save by its effects, as when some inexplicable, unseen poison in the breeze blights the apples and the grain while in the flower, or kills them in the bud, or destroys them when they have reached maturity; as though by the tainted atmosphere in some unknown way spreading abroad its pestilential exhalations. So, too, by an influence equally obscure, demons and angels breathe into the soul, and rouse up its corruptions with furious passions and vile excesses; or with cruel lusts accompanied by various errors, of which the worst is that by which these deities are commended to the favour of deceived and deluded human beings, that they may get their proper food of flesh-fumes and blood when that is offered up to idol-images. What is daintier food to the spirit of evil, than turning men’s minds away from the true God by the illusions of a false divination? And here I explain how these illusions are managed. Every spirit is possessed of wings. This is a common property of both angels and demons. So they are everywhere in a single moment; the whole world is as one place to them; all that is done over the whole extent of it, it is as easy for them to know as to report. Their swiftness of motion is taken for divinity, because their nature is unknown. Thus they would have themselves thought sometimes the authors of the things which they announce; and sometimes, no doubt, the bad things are their doing, never the good. The purposes of God, too, they took up of old (words), from the lips of the prophets, even as they spoke them; and they gather them still from their works, when they hear them read aloud. Thus getting, too, from this source some intimations of the future, they set themselves up as rivals of the true God, while they steal His divinations.

Thus, since the pagan gods were demons, Christians would avoid contact with them as far as possible. Drinking the water and consuming the food offered to pagan deities, sharing baths with pagans, going near a pagan temple - they had a strict policy shunning all such things. If a Christian is starving to the point of death, and the only food that he can see is contaminated by pagan sacrifice, Augustine writes that it is better to reject it and instead die with Christian fortitude (Letter 47). Worship of a different god no longer made one just different or inferior in the eyes of a Christian but it made him demonic and evil. The thoughts of pagans who criticised Christianity were not of their own free will but from the influence of the devil. This excessive obsession with demons, at the distance of a millennium and more, can sound comical but it was not. Nor was it mere rhetoric. It concerned the salvation and damnation of mankind and nothing else could be more important.

Christians saw the arrival of Christ as putting an end to the empire of these demons who had been dominating mankind all this while. When Christ was raised on the Cross at Golgotha, it was his victory over sin and hence it also signalled his triumph over these demons who had led humanity into sin all this while. Christ had performed exorcisms to cast out evil demons from people in the New Testament.

When the Roman Emperor became Christian in the fourth century, Christians saw this political victory of Christianity over the Roman Empire as a reflection and an obvious consequence of the spiritual victory of Christ over the demons. So, the destruction of pagan temples was seen by Christians as a mopping up operation; the exorcism of all demons from their places of residence (pagan temples) once and for all. The destruction of temples also served another purpose. The early Christians who had converted before the coming of Constantine had done so out of sincere conviction and knowing the risks associated with accepting Christianity. So, they avoided the temples of the pagans. But after the establishment of Christianity as the state religion, there was a massive surge in conversions and not all of them would have been genuine. So, there would be a lot of laymen in Christian congregations who would tend to slip into the old errors of pagan worship. This necessitated the destruction of pagan temples.

To destroy a temple was to cancel its majestic presence and to warn others of its negative religious meaning. The precision with which Christians in Egypt mutilated the image of gods and goddesses by carefully hacking away their hands, ears, noses and eyes showed that this was not always the work of fanatics but a premeditated and planned affair. The historian Bart Ehrman generally notes in this regard:

Throughout the empire one can find numerous cult statues not merely destroyed but systematically defaced, subject to bodily mutilation. These mutilations deliver an obvious message. By removing the statue’s eyes, ears, mouth, and nose the Christian antagonist showed in graphic terms that the pagan god could not see, hear, speak, or sense in any way. Hands were lopped off to show the god could not do anything; genitals were mutilated to show it could provide no fertility. The ideology behind such mutilations goes back to biblical times. In the Hebrew Bible we read in Psalm 135:16-17: “16 They [idols] have mouths, but cannot speak, eyes, but cannot see. 17 They have ears, but cannot hear, nor is there breath in their mouths”. But Christian attacks were not limited to destruction. There was also the matter of replacement. Demeas replaced Artemis with a cross. Sometimes Christians who mutilated a statue then scratched the sign of the cross on its forehead. Now the pagan idol had become a witness to Christ. So too with sacred buildings. At other times, statues were simply desacralized, moved from cultic sites and redeployed as objects of art, as seen with Constantine’s decoration of his New Rome and as poetically embraced by the Christian author Prudentius (who writes): Of bloody sacrifices cleansed, The marble altars then will gleam, And statues honoured now as gods, will stand, mere harmless blocks of bronze.

After all, pagan temples were more dangerous than pagan people. The quiet, majestic, immutable, and attention grabbing pagan temples stood in full view visible to all, even from a large distance, as the reminders of the religion of the demons that had swayed mankind for thousands of years.

Paganism in Retreat

The Christianisation of the Roman world and subsequently the rest of Europe was a gradual process taking place over several centuries. The last nations in Europe to convert to Christianity were the Baltic nations of Lithuania and Latvia which was completed only in the 15th century CE. But it all began with a single Roman emperor.

Emperor Constantine

On October 29, 312 AD, the Roman Emperor Constantine stormed into Rome, the Eternal City, fresh from crushing his enemy Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge. The Capitol’s temple altars stood primed for sacrifice, the air thick with the expectation of traditional religious rites to be carried out by the victor emperor to honour the gods. But, to everyone’s surprise, Constantine didn’t pause. No offerings were made and no prayers to Jupiter or Mars or any of the traditional gods. He marched straight to the imperial palace, leaving all the gods waiting. Was it a snub? Was it an oversight? Was it just because he was tired and exhausted? Little did people realize that this was the first tremor of what would be a seismic shift in world history. Constantine then made the claim that would alter the course of history forever. What was the claim?

After his astounding victory in Rome, Constantine claimed that a new god had made him victorious in the battle. Who was this new god? Or… should we say… God? Constantine believed that his victory was due to the blessings of the God of the Christians.

Emperor Constantine (died 337 CE) gave the Church official status in the Empire. The Edict of Milan that he issued in 313 CE enshrined the freedom of worship for all in the Empire after the persecution of Christians by his predecessor. But this did not mean that he was secular. He favoured the Christian church over pagan cults through the following polities :

Constantine ordered the return of all property and church buildings to the clergy who had been persecuted during the time of pagan emperors.

Constantine gave huge grants of land and financial support to the Church. He also gave financial support to allow them to support their congregations.

Aristocrats of the empire had always been obliged by the state to do public service using some of their money in the pagan empire. But Constantine exempted those aristocrats who were Christian clerics from this requirement, and hence Christian cleric aristocrats could accumulate wealth without being required to do public service.

Constantine built the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem after destroying a temple to Aphrodite on that site.

He gave exemptions for churches from paying taxes. All the tax exemptions that churches have enjoyed, and still continue to enjoy to this day, go back to Constantine—so running a church not only had imperial support and sponsorship, but also was a profitable business as it was free from taxation.

He declared Sunday as a public holiday.

He clearly expressed his favour for Christianity in all his orations.

He underfunded pagan temples and pagan worship cults.

He founded a new city named Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul in Turkey) that would serve as the new capital of the Roman Empire in the East (New Rome), and he ensured that it was built as a Christian city, without much pagan influence. Constantinople would serve as the Christian Rome for the new Christian era.

He also encouraged the building of churches on the sites of various martyrs who had died for their Christian faith during the days of the pagan empire.

He banned crucifixion as a form of execution by the Roman state, as by now, the cross had become a sacred symbol for Christianity.

Constantine’s was rewriting the definition of Religio - it was the Christian God, and not the old gods, who delivered not just victory in battle but any kind of benefit—both in this world and the world to come. As a ruthless politician, Constantine erased his rival Maxentius’ memory while keeping Rome’s pagan conservatives comfortable. But to the Christians, he told a different story. In hushed letters, he credited his victory to a singular sign ☧ from their One True God. Years later, writing to Persia’s king Shapur II, he laid bare his soul:

I bend my knee to Him, shunning the blood and stench of pagan altars.

This wasn’t just a conversion—it was a revolution cloaked in Roman robes. Through a decade of savage civil wars, he toppled the divided Roman Empire, seizing the East by—all without a nod to the gods who’d guarded Rome for centuries. His subjects saw it in silence. No sacrifices were made and no temples were visited. The man who held the empire’s fate was now betting on a new divine patron and sponsoring only this new God’s churches and priesthood instead. Constantine’s Christianity wasn’t loud—it was quiet— yet it was a calculated defiance that shook the foundations of a millennia-old world. By the time the Romans came to realise it, they found that their Empire was already rewriting history.

Legal Decline

The first prohibition of pagan sacrifice is attested in a law issued in 341 CE by Constans, the successor of Constantine. He orders :

The madness of sacrifices shall be abolished. For if any man in violation of the law of the sainted Emperor, Our father, and in violation of this command of our Clemency, should dare to perform sacrifices, he shall suffer the infliction of a suitable punishment.

It looks like the law was not rigorously policed and sacrifices continued in Rome for a long time. But, this set a precedent for persecution of pagans and started the ball rolling of the decline of paganism/ A further set of laws between 353 and 360 instituted death penalty for practice of sacrifice, veneration of pagan idols and divination.

It was under the reign of Emperor Theodosius I (r. 379 - 395 CE) that Catholic Christianity was officially declared as the only tolerated religion in the empire. He also instituted the harshest legislations against both the public and private practice of paganism. Sacrifices, the decoration of sacred trees, and the raising of turf altars were made treasonable offences. Pagan holidays dedicated to the old gods were decreed normal working days. It is estimated that at the end of the reign of Theodosius, about half of the Roman population was still pagan. Still, for ambitious people, it was becoming increasingly obvious that being pagan would be increasingly unprofitable and dangerous in terms of career development. Over the next century, Theodosius’s successors continued to issue laws against paganism. Emperor Leo I banned pagans from the legal profession around 468 for instance. But generally there was some degree of religious toleration in the Byzantine Empire of the 5th and early 6th centuries, particularly during the reign of Anastasius (491–518 CE) when it has been estimated that there were more than thirty active religious creeds.

The last major purge of paganism was instituted by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565), as part of a wider political and religious policy of imposing orthodox Christianity on all the subjects of his empire. Pagans were ordered to report to the nearest church, receive Christian instruction and get baptised. The penalty for non-compliance would be loss of citizenship and confiscation of property. Baptised Christians found guilty of participating in pagan practices faced capital punishment. Non-Christians were banned from teaching, and the famed philosophical schools of Athens (including the Academy founded by the philosopher Plato nearly a millennium ago), were shut down in 529. The works of the great pagan classical thinkers were devalued and many of their books confiscate and burnt. Those found guilty of reverting to the old gods were sentenced to work in hospitals, imprisoned in monasteries, or were executed. It should be noted that Justinian’s intolerance extended to heretic Christian sects as well as pagans.

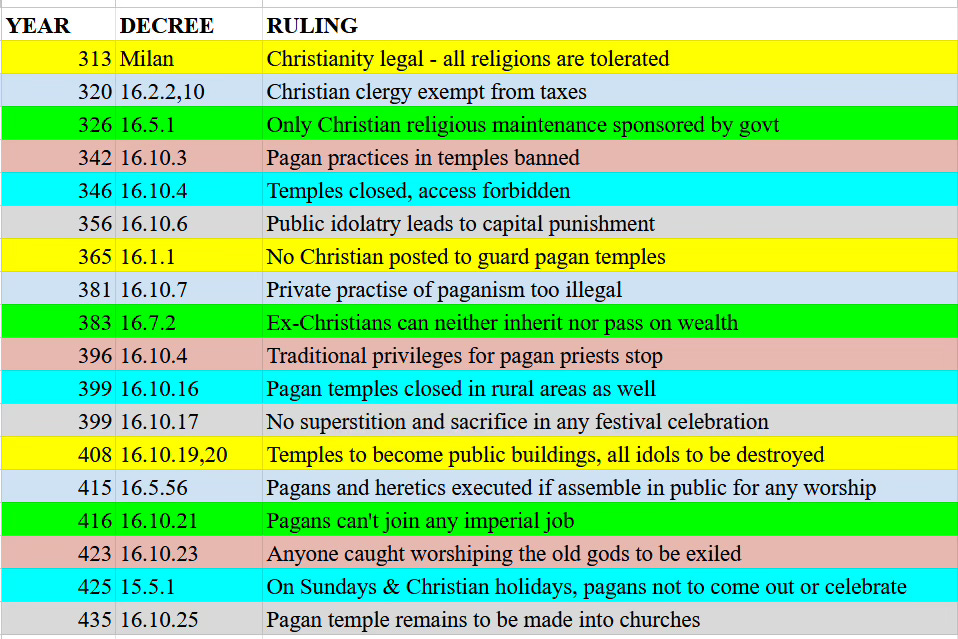

The following image summarises the anti-pagan legislations passed by the Roman Empire.

How to convert pagans

Issuing legal decrees and performing acts of vandalism, such as tearing down pagan temples, was one thing, but convincing entire populations to embrace Christianity was a far more complex endeavour. Even after a nation’s official conversion, the Church faced centuries of resistance from deeply rooted pagan traditions. To achieve this monumental shift, the Church employed a range of sophisticated strategies, blending diplomacy, cultural adaptation, coercion, and education. These methods were not uniformly applied but were tailored to the diverse societies of the Roman Empire and early medieval Europe. This section of the article surveys some important strategies.

Marriage of Pagan Kings to Christian Wives

One of the Church’s most effective strategies was leveraging royal marriages to introduce Christianity into pagan courts. A Christian wife, often from a neighboring Christian kingdom, could influence her pagan husband, his court, and eventually the broader population. These women acted as cultural and religious ambassadors, softening resistance to Christianity through personal influence and political alliances.

Clovis I and Clotilde in Francia (late 5th century): Clovis, king of the Franks, married Clotilde, a Burgundian Christian princess. Clotilde’s persistent efforts, combined with Clovis’s reported vow to convert if victorious in battle (notably at Tolbiac in 496), led to his baptism by Bishop Remigius of Reims, who also promised reinforcements. His conversion prompted the mass baptism of thousands of Franks, setting a precedent for the Christianisation of the Frankish kingdom who would conquer and convert the rest of their Germanic pagan brethren in Germany.

Æthelberht of Kent and Bertha (late 6th century): Æthelberht, a pagan Anglo-Saxon king, married Bertha, a Christian Frankish princess. Bertha’s presence in Kent paved the way for Pope Gregory the Great to send Augustine of Canterbury in 597. Æthelberht’s eventual conversion and support for Augustine’s mission established Christianity in southeast England.

Edwin of Northumbria and Æthelburh (7th century): Edwin, a pagan king, married Æthelburh, a Christian princess from Kent. Her influence, alongside the missionary Paulinus, led to Edwin’s baptism in 627, marking a significant step in the Christianisation of Northumbria.

This strategy worked because royal conversions often trickled down to the nobility and commoners, as loyalty to the king encouraged emulation of his faith.

Hatred of the Priestly Class

Christians have had particular hatred of pagan priests because if the pagan gods are demonic, then pagan priests are central in propagating and maintaining these demonic cults and keeping others deluded by the spell of the Devil. While hatred of priests and legislation targeting them in particular is central to Christian conversions everywhere, it was among the Celtic Irish peoples that it was so visibly seen.

Central to the Celtic society were a group of hereditary priestly people known as the Druids. They were a class of hereditary priests who stored and passed on the oral repertoire of the knowledge of the tribe that included myths, herbs, law, political strategy, etc. They were purely oral and in fact saw writing as an inferior tool of transmitting knowledge. The missionaries saw the Druids as the biggest hurdle in conversion! They began to vilify the Druids & accuse them of exclusivity of their knowledge and performing sorcery to deceive the people ! So, vilification of the Druids as evil sorcerers and conflict between Druids and missionaries is a recurring theme in Irish Christian hagiographies. Muirchú’s “Life of St. Patrick” portrays Druids as magicians who attempted to outmatch the missionary Patrick’s miracles, only to be defeated by divine power. For example, one story describes a Druid named Lochru being lifted into the air and dashed to the ground by Patrick’s prayers, a narrative designed to demonstrate Christianity’s superiority. Look at a painting of a converted British family sheltering a missionary while the evil Druid lurks outside looking to persecute them.

The Druids lived closer to the holy sites of Celtic paganism - “sacred wells“ filled with spirits of the spring that had healing powers and were considered “the source of life”. After Christianisation, all these holy wells were reused and their healings were attributed to some Christian saint. The holy water began to be used for Christian baptism instead. Christian crosses were carved on sacred stones to be reused for Christian worship purposes.

Building Monasteries

Monasteries were not just centres of worship but also hubs of education, charity, and cultural transformation. The Church established monasteries in remote and rural areas, where pagan practices were deeply entrenched, to serve as beacons of Christian life and learning. Monks demonstrated Christian virtues, provided social services, and gradually won over local populations.

Iona in Scotland (6th century): Founded by St. Columba in 563, the monastery at Iona became a base for missionary work among the Picts and Scots. Its monks spread Christianity through preaching, education, and diplomacy, influencing northern Britain.

Fulda in Germania (8th century): St. Boniface established the monastery at Fulda in 744 as a center for converting the Germanic tribes. Fulda’s monks trained missionaries, preserved Christian texts, and engaged with local communities, weakening pagan resistance in the region.

Lindisfarne in Northumbria (7th century): Founded by Aidan in 635, Lindisfarne served as a missionary outpost for converting the Anglo-Saxons. Its monks combined asceticism with outreach, making Christianity accessible to rural populations.

Monasteries were strategic because they offered a visible, stable Christian presence, contrasting with the often decentralized nature of pagan worship.

Monks and Bishops Destroying Rural Pagan Shrines

While persuasion was preferred, the Church sometimes resorted to direct action against pagan sacred sites. Monks and bishops, often acting with royal or local support, destroyed rural shrines, sacred groves, and idols to disrupt pagan worship and assert Christian dominance. These acts were symbolic, signaling the power of the Christian God over pagan deities.

St. Martin of Tours (4th century): In Gaul, Martin, a former soldier turned bishop, aggressively destroyed pagan temples and sacred trees, often replacing them with churches. His actions, though provocative, demonstrated Christianity’s growing authority.

St. Boniface and the Donar Oak (8th century): Boniface famously felled the sacred oak dedicated to the Germanic god Donar (Thor) at Geismar in 723. Apparently, the lack of divine retribution impressed the local Hessians, many of whom converted, and a chapel was built on the site.

Charlemagne’s campaigns in Saxony (8th century): During the Saxon Wars, Charlemagne ordered the destruction of the Irminsul, a sacred tree revered by the pagan Saxons as the centre of the world. This act, combined with forced baptisms and slaughter of those who did not comply, aimed to break Saxon resistance to Christianity.

While effective in some cases, this strategy risked alienating populations, requiring careful follow-up with missionary work to sustain conversions.

Assimilation of Pagan Temples and Rituals

Rather than eradicating all traces of paganism, the Church often co-opted pagan sites, rituals, and festivals, giving them Christian meanings. This strategy of accommodation made Christianity more familiar and palatable to pagan converts, easing the transition. For example, when St Augustine of Canterbury wrote to Pope Gregory regarding what to do to the pagan temples and rituals of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Kent whose king he had just converted, he replies :

Tell Augustine that he should by no means destroy the temples of the gods but rather the idols within those temples. Let him, after he has purified them with holy water, place altars and relics of the saints in them. For, if those temples are well built, they should be converted from the worship of demons to the service of the true God. Thus, seeing that their places of worship are not destroyed, the people will banish error from their hearts and come to places familiar and dear to them in acknowledgement and worship of the true God. Further, since it has been their custom to slaughter oxen in sacrifice, they should receive some solemnity in exchange. Let them therefore, on the day of the dedication of their churches, or on the feast of the martyrs whose relics are preserved in them, build themselves huts around their one-time temples and celebrate the occasion with religious feasting. They will sacrifice and eat the animals not any more as an offering to the devil, but for the glory of God to whom, as the giver of all things, they will give thanks for having been satiated. Thus, if they are not deprived of all exterior joys, they will more easily taste the interior ones. For surely it is impossible to efface all at once everything from their strong minds, just as, when one wishes to reach the top of a mountain, he must climb by stages and step by step, not by leaps and bounds....

Temple Conversions in Rome (6th–8th centuries): The Pantheon, originally dedicated to all Roman gods, was converted into the Church of St Mary and the Martyrs in 609 CE. This preserved the site’s cultural significance while redirecting worship to Christianity.

Christmas and Saturnalia: The Church aligned the celebration of Christ’s birth with the Roman festival of Saturnalia (late December), incorporating elements like feasting and gift-giving. This made the transition to Christian holidays smoother for Roman converts.

Brigid’s Transformation in Ireland (5th century): The Celtic goddess Brigid was reimagined as St. Brigid, of the same name, with her sacred wells and festivals Christianized. Kildare, a major pagan site, became a Christian monastic center under her patronage.

This strategy was particularly effective in regions with strong cultural traditions, as it preserved community identity. So, the Church preserved the outward rituals and places of this cultural tradition to preserve their outward communal identity while depriving their original pagan significance and substituting it by Christian theology.

Introducing a Religious Dimension in Wars

The Church often framed military conflicts between pagan and Christian kings as holy wars, encouraging Christian kingdoms to conquer and convert pagan neighbours. This strategy intertwined religious and political goals, presenting conquest as a divine mandate.

Charlemagne’s Saxon Wars (772–804): Charlemagne’s campaigns against the pagan Saxons were justified as a mission to spread Christianity. After defeating the Saxons, he enforced mass baptisms and established churches, though resistance persisted for decades.

The Northern Crusades (12th–13th centuries): The Teutonic Knights waged crusades against the pagan Balts and Slavs in the Baltic region. The conquest of Prussia and Livonia was accompanied by forced conversions and the establishment of Christian institutions.

Olaf Tryggvason in Norway (10th century): King Olaf I used military force and coercion to convert Norway’s pagans, often framing his campaigns as battles for the Christian faith. His efforts, though brutal, accelerated Norway’s Christianisation.

This approach was effective in expanding Christian territories but often led to superficial conversions, requiring further missionary work to deepen faith.

Divide and Rule: Exploiting Rivalries

The Church capitalised on internal divisions within pagan societies, such as rivalries between factions or heirs, to promote Christianity. By aligning with one side that was more conducive to it, the Church gained influence and secured conversions.

Francia’s Merovingian Dynasty (6th century): The Church supported certain Merovingian kings perceived to be more supportive towards it, over others, leveraging dynastic disputes to strengthen its position. Bishops often mediated conflicts, gaining influence in the process.

Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy (7th century): In England, the Church exploited rivalries between kingdoms like Northumbria and Mercia. By supporting Christian kings, such as Oswald of Northumbria against the pagan king of Mercia whom he was fighting, the Church gained footholds in contested regions.

Lithuania’s Conversion (14th century): The Church used the rivalry between the pagan Grand Duke Jogaila and his cousin Vytautas to secure Lithuania’s conversion. Jogaila’s marriage to the Christian queen Jadwiga of Poland in 1386 led to his baptism and Lithuania’s official Christianization.

This strategy was effective in politically fragmented regions, where the Church could act as a unifying alliance building force under Christian auspices or exploiting the conflict to secure its influence.

Securing the Next Generation

The Church recognised that long-term success depended on shaping the beliefs of future kings, leaders, and nobles. By educating the children of pagan rulers in Christian institutions, the Church ensured that the next generation would be predisposed to Christianity, even if the current generation only converted superficially or relapsed.

Anglo-Saxon Princes in Rome (7th century): Pope Gregory the Great encouraged the education of Anglo-Saxon princes in monastic schools in continental Europe or Ireland, where they were exposed to Christian teachings. This helped sustain Christianity in England’s emerging kingdoms.

Charlemagne’s Court School (8th century): Charlemagne established a palace school at Aachen, where the sons of Frankish and allied nobles were educated by Christian scholars like Alcuin. This ensured that future leaders were steeped in Christian values.

Vladimir the Great’s Heirs in Kievan Rus’ (10th century): After Vladimir’s conversion in 988, his children were educated in Christian institutions, ensuring the continuation of Christianity in Rus after his death.

This strategy was a long-term investment, creating a Christian elite that would perpetuate the faith across generations.

Missionary Preaching : Miracles & Material Support

Missionaries like St. Patrick in Ireland and St. Augustine in Kent used preaching and alleged miracles to demonstrate the power of the Christian God. Patrick’s legendary confrontation with druids at Tara in the 5th century, where he reportedly outperformed pagan rituals, won converts through awe and persuasion.

The Church offered material support to converts, especially in times of crisis. Monasteries provided food, shelter, and medical care, attracting pagans to Christianity. For example, during famines in Anglo-Saxon England, monasteries like Wearmouth-Jarrow distributed aid, associating Christianity with generosity.

Legal Reforms

The Church organized synods to codify Christian practices and outlaw pagan ones. The Council of Tours (567 CE) in Gaul banned certain pagan rituals, while Charlemagne’s “Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae” (785 CE) imposed harsh penalties for pagan practices including death, thereby reinforcing Christian norms.

Thus, the Christianisation of the Roman Empire and the rest of Europe was a slow, arduous, and multifaceted process that required the Church to adapt its strategies to diverse cultural and political contexts. By marrying Christian princesses to pagan kings, building monasteries, destroying pagan shrines, assimilating traditions, framing wars as holy, exploiting rivalries, educating future leaders, and employing additional tactics like preaching and charity, the Church gradually transformed the spiritual landscape of Europe. These strategies were not without flaws—coercion sometimes bred resentment, and assimilation risked diluting Christian doctrine—but their combined effect was undeniable. Over centuries, the Church turned a patchwork of pagan societies into a predominantly Christian continent, leaving a legacy that continues to shape Western civilisation.

What a post ! I've read each and every word and learnt a lot.

The parallels between Paul and Mohammad were striking about the "Abraham" or how the world has only one God but people became idol worshippers. Muslilms call it as "reverts". I mean I know Mohammad copied a lot because he was part of the same religous landscape but knowing that Paul is the originator is striking.

In all of the commentary more has to be written about the pscycological condition or spiritual piety of the believers in the event a shock or a trauma. For ex: When Neo Babylonians forced jews to exile, obviously it was a shock to the jews and were in the deepest trauma of asking:

"Why did the yehowah abondoned us ? Is he not more powerful than Marduk?"

"No, that can't be true. Yehowah is powerful than any god, but why did this destruction happend to us"?

"Unless, it is the work of yehowah himself. Yehowah did this for us a matter of punishment for committing sins".

"It's not about Yehowah being more powerful than any other god, it's that there is no other god. If there is any other god, it would mean our defeat at the hands of Neo Babylonians would be credited to that god Marduk".

"Our defeat can only be explained if Yehowah is the ONLY one true god and our defeat is a punishment for committing sins"

"From this day, we are only going to worship Yehowah and reject every other god".

In the similar way, I could see how Jews who considered Jesus as as the Saviour reintrepreted his death.

"He was supposed to be our saviour. But he died".

" How can we explain that. He was our Saviour".

"Unless, Unless, He SAVED us through his death".

"Yes, he saved us through his death".

I also learnt about how ancient greek phislophers were essentally saying "Ekam Sat viprah Vadanti".

Do you recommend any book that talks about pscycological aspects and the propensity of the brain to explain away unfavourable situations by ridiculous rationalizing in the even of trauma? Entire Judaism and Christianity was invented based on the above phenomenon.

PS: As you know idea of Satan (along with angels) came to Jews from Zorastraians. Add that line if you wish